Swift Creek Séance at Washington’s Mt. St. Helens

May 24th, 2012

One foot in front of the other, again and again.

In the 1840s, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were some of the first American writers to appreciate the wealth and vastness of natural wonders in the still-wild United States. Writing and speaking extensively during their era, they ushered in a more spiritual, conservation-minded mode of thought relating to nature and the wild.

Except Emerson and Thoreau never bothered to hike up Mt. St. Helens. Had the famed American naturalists spent any time on the slopes of a decent-sized Cascade hill, they would’ve realized instead of holistic inspiration, the trip reduces one’s universe to a small, nearly annoyance-free scale of the task at hand: one foot in front of the other, again and again. Perhaps some may find a kind of Zen in the exercise.

This kind of hiking is a blissful, silent world without cellphones or traffic, without fevered egos or the constant assault of media. Only the sound of crunching, grinding snow and a mixture of cinders, gravel and ash under one’s feet. Everything else, flowery prose and all, falls by the wayside. Basic motivations like food, rest, movement, exploration and challenge all vie for attention. The views are pretty good too.

Mt. St. Helens, Weather Maker and Volcano

Though not a technical climb, and comparatively smaller even before its catastrophic 1980 blast than its Cascade neighbors Rainier, Adams and Hood, Mt. St. Helens is no slouch. Like all Cascade peaks St. Helens is a weather maker, and remains unpredictable as moist air, fresh off the Pacific, is suddenly jammed up several thousand feet by the spine of the Cascades, super-cooled, and condensed. This results in a gamut of meteorological goofs, the least of which being sudden storms at high altitudes any time of the year.

There’s nothing like being socked in by fog, or moisture which curiously hasn’t had time to coalesce into a cohesive fog, while gale-force winds blister the back of your neck with the rattle and snap of your jacket collar, sandblasting ash into every exposed pore.

Depending on the time of year at St. Helens, avalanches are also a very real danger, and crevasses and snow bridges often lurk just below placid snowfields. Trail markings easily become lost under massive snowdrifts early in the season, or simply vanish into oblivion. Icefields can crop up when least convenient as well, so while crampons are generally not necessary to make it to the top of St. Helens’ rim during the summer, they’re certainly good to have for the unexpected, and conditions can change drastically from year to year. More than one enthusiastic Mt. St. Helens outing has been forced back or into confusion by the mountain’s bad side since the south face was re-opened to hiking in 1987.

When our group of friends and Seattle-area work colleagues initially met to discuss a trip up St. Helens one January afternoon, it seemed June would be an excellent time to go. Several people in our party had tried the mountain earlier in the spring the previous year, and found themselves to be one of the aforementioned enthusiastic parties which had to turn back when conditions became impossible. We figured June would fit the bill, as snow in the high country would still be relatively frozen from its wintertime solace, thereby reducing the risk of avalanches and crevasses, and permits would be readily available before the full-on summer stampede of July and August.

The consensus was also the weather would be reasonably consistent by June. After all, June is the beginning of summer, even in the Pacific Northwest right?

A Weekend Warrior Adventure, Further Condensed

So much for making plans in January. A record snowfall blanketed the Cascades this particular winter, and hadn’t even begun to recede when we made our way to the south face of St. Helens for our hike on June 12th.

Having conditioned throughout the spring on several steep Western Washington trails, particularly repeated treks up the Muir Snowfield to Camp Muir on Mt. Rainier and quick, half-day affairs at local favorites like Mt. Si, McClellan Butte and Mt. Pilchuck, we knew our St. Helens trip would in no way be snow-free. In fact, as our date approached, Forest Service roads leading to the campsite and trailhead north of Cougar remained snowed in, necessitating us to build in time hike five miles to the Climber’s Bivouac campsite over snow-covered roads.

While this didn’t come as a shock, it did require some last-minute juggling. Picking up our permits at Jack’s Restaurant in Amboy the morning of June 12th, we arranged for an additional day with the sympathetic staff. The plan was to drive to the snowline on Forest Service Route 81 and park, hike to the Climber’s Bivouac at the end of Forest Service Route 830, spend the night, summit the next day and hike out back to our cars.

We were originally planning on going up the mountain on June 12th, a Saturday, but now we would be going up the mountain and hiking back out of the bivouac to our cars all on Sunday, June 13th. A very full 24 hours. Clearly, Monday morning was going to be lousy for all involved, but no one seemed to mind. After all, what are sick days for?

Mysterious Warm Updrafts and Interrupting Adams’ Domain

The trek in was long but enjoyable. Hiking on a graded, finished roadway buried under six feet of snow removed the annoyance of tree wells, but conditioned as we were, slogging through the snow made the march up the mild grade to the Climber’s Bivouac a little more tiring as the day wore on. Views of Mt. Adams and Mt. Hood were plentiful, however, and the weather was stellar as we creeped further and further into the backcountry.

Soon we encountered the mysterious warm updrafts and downdrafts of the wild forest, blowing in from holes in thick patches of trees along the road, as the clear, blue sky gave way to high overcast clouds which eerily reflected the glow of the snow into the late afternoon.

As we reached the Climber’s Bivouac, the weather had grown strangely still, like it was getting ready to rain. The mysterious warm breezes came and went as we prepared camp on top of several feet of snow, eyeballed maps and boiled water for the next day, all under the watchful gaze of St. Helens’ south face. At times the air grew so still it seemed as though the mountain could hear our every word. After a light dinner punctuated by many hearty laughs, daylight gave way to a gray evening. I wandered about 50 yards east of the Climber’s Bivouac to find a little quiet from our party.

Moving through the crunchy, deep snow from tree to tree, avoiding the deep wells while carefully looking back at my footsteps and keeping compass in hand, I reached a high ridge and slowly surveyed the broad Swift Creek Valley below. As I looked up, I suddenly caught the awesome gaze of nearby Mt. Adams, dwarfing over me as though I’d silently interrupted the giant’s still domain.

I swallowed hard, rocking back and forth on my heels as Adams looked me over, it’s squat, truncated summit curling to the north. The great mountain’s form drifted into the high, gray overcast skies. The warm breezes returned, echoing through an opening in the woods to my right. Alone in the wilderness, Mt. Adams cast a spell.

Ghostly patches of light remained in the sky throughout the night.

Once, on a clear night in 2000 during another visit to Mt. St. Helens, I saw a fireball shoot across the sky and light up the night over Mt. St. Helens. The fireball was clearly a meteorite, very close, but so close I could feel the object’s velocity as it cut through the night sky. I’d stepped away from my friends and camping colleagues for just a moment to relieve myself, and while walking back saw the meteorite. I could hear it sizzling as it shot over me before dying a sudden death in the atmosphere an instant later.

None of my friends had seen it.

Clear Skies Heralded

Following a brief drizzle, the high clouds and overcast sky remained at daybreak. Starting off we took advantage of the late-season snowpack to make a detour off Ptarmigan Trail 216A on the way to the treeline at the base of Monitor Ridge, and made a cross-country scramble up an improvised ridge trail in the snow just east of the Swift Creek lava flow (I do not advise this during non-snow conditions or without proper compass and map-reading skills).

By the time we reached the treeline at 4,000 feet, we could see a long band of blue to the west, heralding clear skies. The overcast weather kept the heat to a minimum during the morning hours, but by the time we reached Monitor Rock around mid-morning, the sun was blazing away at us, reducing our layers and sending us fumbling for sunscreen. As on the many trips up the Muir Snowfield at Mt. Rainier, standing in a clear, white reflective snowfield without the benefit of tree cover, the heat quickly built, leaving us feeling more like Lawrence of Arabia in the desert than heading into Cascade high country.

Slowly, steps at a time, we cleared ridge after ridge, as well as all the extra ridges which seem to pop up in between. The summit crest would begin to look enticingly close, then fall away into perspective as one adjusted to the appropriate depth perception in the treeless environment. A misplaced detour to the west at about 7,000 feet landed us at the northern tip of a steep icefield between the remains of the dwindling Swift and Dryer Glaciers (both beheaded in the 1980 blast), where the surface resembled a million spilled buckets of ice.

A few sphincter-clenching moments later we had worked our individual way about and around it, though a slip would’ve meant a long, bumpy, humbling tumble down unless a self-arrest was quickly made. Then, as we climbed to the top of the icefield, we realized we were standing on a slow-moving mudslide, and quickly routed back east towards the rocky lava tongue highlighting the east tip of the Monitor Ridge trail.

We began our final trek to the summit on the sharp-rocked lava tongue hoping to avoid the increasingly slick snow cover, but like any snowbound climber eventually wound up back on the more forgiving white stuff, trudging upwards, kick-stepping up the steep incline all the way.

At one point, the summit only looked as far as away as the length of Seattle’s Queen Anne Hill or San Francisco’s famous Lombard Street drop. Not even a fellow hiker’s exploding boot (remedied by some available duck tape at the summit – never leave home without it) slowed us down. Finally, at long last, we reached the top, and for our troubles nearly walked into the crater out of sheer momentum.

When Superlatives Fail, Silence Will Do

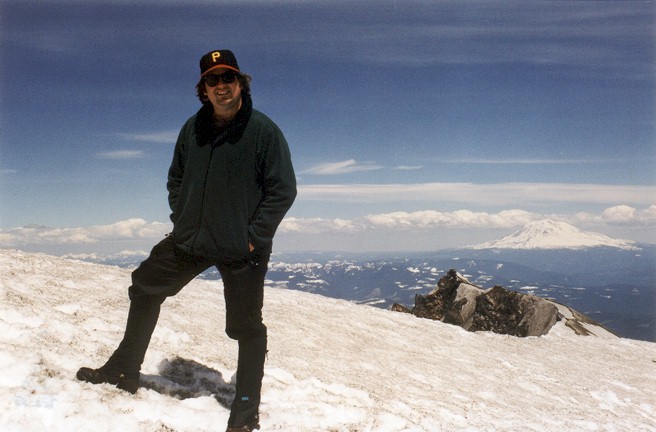

The view was immense, and worthy of a dictionary full of superlatives. Spectacular. There’s nothing like the view from a high peak, and from a Cascade high point you can see everything.

From Mt. St. Helens’ summit rim giant Mt. Rainier stood bisected by clouds to the north; Mt. Adams’ wise and giant form overlooked us to the east, directing the eyes towards the vast expanse of Eastern Washington into the Yakima Valley; Oregon’s shining Mt. Hood pointed up from the to the south. We could also see smog over Portland, the bend in the Columbia River at Longview to the southwest, and to the northwest, ever so far away, the seemingly puny Olympic Mountains.

We stayed at the summit for about 45 minutes, trying to stay off the overhanging cornices of snow but probably walking on them anyway, eyeballing the 1,000 ft. high Lava Dome below and taking hundreds of photographs. We wound up with a cluster of terrific group and individual shots, and rewarded ourselves with a well-deserved gaze upon the views below. Looking downhill from the rim we could see the Climber’s Bivouac, our tiny tents sitting as still as when we left them in the early morning. A Coast Guard helicopter made a brief appearance, as did an airplane which maniacally buzzed the summit at one point and waved, then seemed to fly carelessly around the crater below us.

Any hiker who’s been around will tell you going down is often more difficult than going up, as steep downward slopes are where the real wear and tear on your body takes place, particularly on your knees and ankles. Fortunately, heading down St. Helens tended to much easier than going up in this particular snowy year, and we managed to glissade down the length of the mountain like a giant waterslide, saving our knees, and in particular my achilles, which by then was humming like a high-tension power line.

My ice ax made steering down some of the snow chutes and keeping some semblance of control easier, but our last glissade chute turned out to be a very steep one indeed, nearly amusement park ride-worthy. I was one of the last to go down, and my trepidation turned to goofy delight when gravity took over, plowing me into a pile of snow at the bottom where my friends were waiting for me.

Though not all glissade chutes should be approached with the same frivolousness, when I got back up I was splattered in snow, wet, exhausted, and laughing so hard it ached my face and stomach. No one went to work the next day.

Everyone had forgotten what day it was.